Few American filmmakers have been as independent as Stanley Kubrick in navigating the studio structure of the American film industry. Throughout the course of his 48-year career, Kubrick has amassed a canon of 16 films, which have contributed to his international stature. He now has complete creative control over his films, overseeing their creation from the very beginning with scripting and planning to the very end with the last cut of the editor’s scissors, something that was previously believed to be the domain of foreign directors such as Bergman or Fellini.

“The invulnerability of the majors was based on their consistent success with virtually anything they made. When they stopped making money, they began to appreciate the importance of people who could make good films,” Kubrick said in response to a question about why he believed the big cinema companies had chosen to grant directors like himself broad artistic latitude. One of the filmmakers they went to was Kubrick, but only after he was prepared to take on the challenge and had studied the craft from the bottom up.

In this article, we will mention Kubrick’s first works and his first steps to the cinema Olympus.

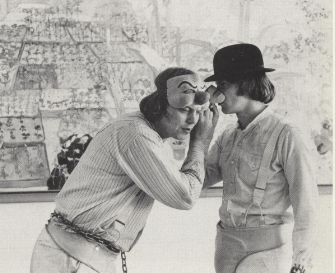

Born on July 26, 1928, in the Bronx, Kubrick started selling photos to Look magazine while attending Taft High School and joined the crew following his graduation. DAY OF THE FIGHT (1950), about boxer Walter Cartier, and FLYING PADRE (1951), which he recalls as focusing on “a priest in New Mexico who flew to his isolated parishes in a Piper Cub,” are the two documentaries he produced for RKO once he ultimately developed an interest in filmmaking. After that, he was able to obtain funding for two low-budget films that, in his words now, were “crucial in helping me to learn my craft,” but he would rather forget about them otherwise. He was the director, editor, sound guy, and cameraman for both of his own films, doing most of the work by himself. The earliest of them, titled FEAR AND DESIRE (1953), was about a pointless military patrol in an undisclosed conflict. Kubrick was happily pleased when the movie hit the art house circuit and received some really positive reviews. It was back to boxing in KILLER’S KISs (1955), telling the tale of the fallur fighter’s inability to rise beyond his impoverished upbringing. By all accounts, Kubrick managed to breathe new life into this ordinary plot with some spectacular footage that included two crucial fight sequences, one in the ring and one at the movie’s finale in a mannequin factory (though he himself will not speak much about either of his first two projects). “It was a profitable film for United Artists,” he comments, “though it was mostly released as a second feature.

Then, in 1955, Kubrick met ambitious producer James Harris through a mutual friend, and the two of them collaborated on THE KILLING. Kubrick’s carefully constructed narrative, which is based on Lionel White’s novel Clean Break, follows a bunch of small-time criminals as they get ready to steal a racetrack. The heist is captured on camera in all its split-second timing and precision (recently replicated in the 1969 Jim Brown car, THE SPLIT, in a lackluster manner that makes one admire THE KILLING even more). The film’s true brilliance, though, is in the ensemble performance that Kubrick managed to extract from a cast of competent Hollywood supporting performers who were seldom given the opportunity to truly act. According to Kubrick, “the budget was larger than the earlier films $320,000.” “This time we could afford good actors such as Sterling Hayden.”

Hayden was the gruff caper organizer; Jay C. Flippen was the cynical group elder; and Elisha Cook, Jr. was the shy husband who, apparently unable to satisfy his voluptuous wife (Marie Wind sor), seeks to wow her with pilfered money. They assisted Kubrick in establishing the film’s gruesome mood, which intensifies towards the wry ending in which Hayden’s luggage bursts apart as he prepares to board an aircraft and the pilfered cash scatters across the beautiful Hayden was the gruff caper organizer; Jay C. Flippen was the cynical group elder; and Elisha Cook, Jr. was the shy husband who, apparently unable to satisfy his voluptuous wife (Marie Wind sor), seeks to wow her with pilfered money.

They assisted Kubrick in establishing the film’s harsh mood, which culminates in a humorous denouement when Hayden’s luggage bursts open right before takeoff and the pilfered cash scatters across the gusty runway à la TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE.

In addition to making a respectable profit, THE KILLING also led Time magazine to make the now-famous claim that Kubrick “has shown more imagination with dialogue and camera than Hollywood has seen since the obstreperous Orson Welles went riding out of town.” After that, Kubrick started working on a screenplay after obtaining the rights to Humphrey Cobb’s 1935 book, The Paths of Glory, which he had read in high school. However, no significant studio was willing to finance the movie.

“Not because it was an anti-war film,” he continues, “they just didn’t like it.” Subsequently, Kirk Douglas consented to feature in the movie, and United Artists provided $935,000.

Even with the current deluge of anti-war movies, PATHS OF GLORY (1957) remains one of the most unwavering representations of the genre. The actions of French colonel George Macready, who orders his soldiers to carry out a suicidal charge in an attempt to obtain a promotion, epitomise the horrifying negligence of leaders for their men. the lines on their own fellow soldiers.

In the movie, “untinchingly like darting into close-up to capture the indignation on an officer’s face, advancing relentlessly at eye level towards the stakes against which the condemned opes to describe the wholesale slaughter of a division,” Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas) is forced to watch while three deserters are chosen almost at random from the ranks to be court-martialled and executed for desertion of camera. Irony, both spoken and visual, abounds in the film. One of the condemned men laments that the cock is still alive in the scenario when he is about to be executed. Saying this, one of his friends uses his fist to squash the bug. “Now you’re one up on him.” To Kubrick’s immense credit, the movie closes with a message of compassion and hope. Love in Dax during the war, guided by a shy German girl in captivity. A German actress named Suzanne Christian, whose true name was Suzanne Christiane Harlan, performed the part. She is currently played by Adophe Menjou, who plays Dax’s senior officer, who is adamant that he must go with the court martial despite his personal concerns, also provided one of his greatest performances in the movie. The movie was filmed in a Munich studio. Menjou was irate with Kubrick when he insisted on doing a sequence many times.

“No such incident occurred on the set of PATHS OF GLORY,” is a statement that is accurate regarding the difficulties Charles Laughton Kubrick had when filming SPARTACUS (1960), a spectacle about enslavement in pre-Christian Rome.

On SPARTACUS, however, Kubrick’s greatest obstacle was star-producer Kirk Douglas. “SPARTACUS is the only film over which I did not have absolute control,” Kubrick stated. “Anthony Mann started the film and shot the first scene, but he decided to depart after the first week of filming due to his differences with Kirk. I hadn’t directed a picture for two years when the movie came out. “When Kirk offered me the job of directing SPARTACUS, I thought that I might be able to make something of it if the script could be changed. But my experience proved that if it is not explicitly stipulated in the contract that your decisions will be respected, there’s a very good chance that they won’t be. The script could have been improved in the course of shooting, but it wasn’t. Kirk was producer. He and Dalton Trumbo the scriptwriter and Edward Lewis the executive producer had it their way with the script and the casting.”

SPARTACUS proved to be one of the best spear-and-sandal epics, and Peter Ustinov eventually earned an Academy Award for his portrayal, despite the issues that plagued the film’s production.