November 2 is the birthday of Luchino Visconti. We review the filmography of one of the most controversial directors—film classics.

Visconti is now regarded as a classic of the world culture of the twentieth century, which has done a lot not only for the cinema, but also for the drama theater, and the opera stage, influenced several generations of directors: From Bob Fosse and Francis Ford Coppola to Bernardo Bertolucci and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. But during the life of the director his films, plays, political views and aesthetic position caused a lot of debate.

The key word in Visconti’s biography is “contradiction”. One of the most decorated aristocrats in Europe, the bearer of the surname mentioned in the “Divine Comedy” of Dante, a descendant of the Milanese counts who ruled the city in the 13th and 15th centuries, this respectable young man, who grew up in abundance and luxury, was in Paris in the late 1930s. Coco Chanel introduced him to French film director Jean Renoir. Visconti volunteered to help the band with the costumes (it turned out that the Paris department store Samaritaine he knows as his five fingers), and then became Renoir’s assistant in several paintings. During filming, he literally got infected with leftist ideas, returned to fascist Italy a new convert Marxist and immediately joined the Resistance, making his villa an underground anti-fascist headquarters. For the rest of his life, he will remain both a refined aristocrat and an ardent communist.

His films are full of contradictions and paradoxes. In order to name the style of Visconti’s first work “Ossessione”, his editor Mario Serandrei coined the word “neorealism”. Visconti – along with Rossellini, De Sica, De Santis – became one of the main elements of this direction in the Italian film of the 1940s-50s, which showed the poor life of the common man in real, not studio interiors and on war-torn streets. But soon Visconti suddenly cease to be interested in the working suburbs: the action of his films flows into the world of balls, secular living rooms, opera convention and the tragic heat of passion. It was as if he lived in several epochs and considered his sovres not only Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre, but also Giuseppe Verdi, William Shakespeare, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Anton Chekhov, Thomas Mann and Marcel Proust.

His films are multilayered, refined, decorative, filled with numerous references to the history of theatre, music, literature, combine the simple simplicity of neorealism, the sublime spirituality of romanticism, the sickness and pessimism of decadentism. All this makes the director’s paintings, on the one hand, difficult to perceive, and on the other – incredibly attractive. Visconti should not just be watched, it should be reviewed: from time to time to return to his films and with surprise to discover those facets and details that have gone unnoticed.

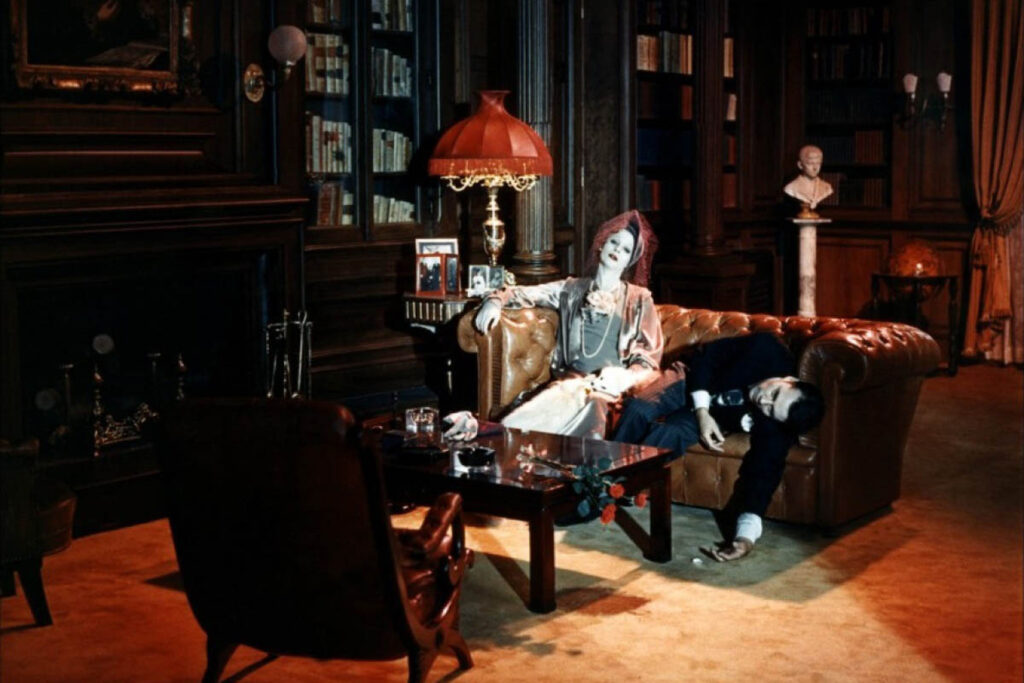

From one of his main films – “La caduta degli dei” (1969). At first glance, this is a classic costume drama. The mid-1930s, Germany. In the family of steel magnates von Essenbeck, whose position and power seem unshakable, the SS Aschenbach appears. He skillfully pits the members of this large family, getting rid of some and throwing bullets at others. The main goal of this cruel game – the heir of all wealth von Essenbeck Martin (Helmut Berger). He must become a docile puppet in the hands of the Nazis.

Visconti fills the film with authentic historical details, the Recon is a real event – “Night of the Long Knives”, a secret operation in which on Hitler’s orders the leaders of the SA assault squads suspected of conspiracy were killed. And at the same time switches the genre register from drama to tragedy with Shakespearean passions and references to classic tragedies—from “Tsar Oedipus” Sophocles and “Medea” Euripides to “Macbeth” Shakespeare and “Faust” Goethe. In addition, the film has the story echoes of “Demons” by Dostoevsky and “Rings of Nibelung” by Wagner. The title of the film refers directly to the last part of the Wagnerian tetralogy, “The Death of the Gods”.

The director combines the family drama with the history of the country, and then with the history of mankind, gradually shifting from the close-up to the general. ” The destruction of the gods” is an exploration of the nature of power that corrupts anyone who touches it.

At first, the film was regarded as irrelevant, heavy, allusion-laden stylisation: all the world talked about Soviet tanks in Prague and student protests in Paris, and Visconti hid from reality in his “ivory tower”. But a few years later, when “Il Conformista” Bertolucci and “Salo, or 120 days of Sodom” Pasolini came out, the relationship to the painting changed. It became clear that Visconti had discovered a very important and relevant topic in Italian cinema. He was the first to question the psychotic nature of fascism, talking about the fact that the basis of the furious lag between “norms” and “purity”, the sifting of “good” from “bad” is actually a deviation from the norm that the Nazis so hide – perhaps from themselves. Against the background of the rise of the neo-fascist movement in Italy in the late 1960s and early 1970s, this was a radical statement. Bertolucci and Pazolini strengthened him and made him even more audible.

After “La caduta degli dei”, it is best to watch three early films in which Visconti creates a transparent aesthetic of neorealism and plans to go beyond it. The film “La terra trema” (1948) is dedicated to Sicilian fishermen who defy seafood buyers: the Valastro family does not want to give for a pittance fish to intermediaries and begins to trade directly. Filmed in the town of Aci-Trezza, the action takes place in the homes of real, really poor people, all characters are played by unprofessional actors, the plot is interrupted by documentary episodes showing the life of fishermen. The film “La terra trema” was released three years after the manifesto of neorealism—Roberto Rossellini’s work”Rome, the Open City” (1945) – and was perceived as the most radical manifestation of this style.

The fact is that Rossellini, like many other directors, in the old-fashioned way attracted professional actors, Visconti refused them, blurring the line between game and non-game movies: it is not always clear where fishermen play the script, and where do everyday business, while the camera watches them. The documentary and organic impression is reinforced by the fact that the actors speak their native Sicilian dialect.

In the “Bellissima” (1951) – perhaps the easiest to perceive Visconti’s film, already starring Italian film star Anna Magnani and film director Alessandro Blazetti (as himself). It is the only Visconti film with comic elements. The action takes place right in the studio: the heroine, Magnani tries to make her six-year-old daughter a star. In the world of cinema the heroine sees exorbitant ambitions, multistory intrigues, under-the-table wars for the attention of the producer and director—all this Visconti portrays with irony. In “Belissima” he departs from the canons of neorealism, putting the focus of the plot not the survival of a little man in a cruel world, but the complex character of Magnani’s role.

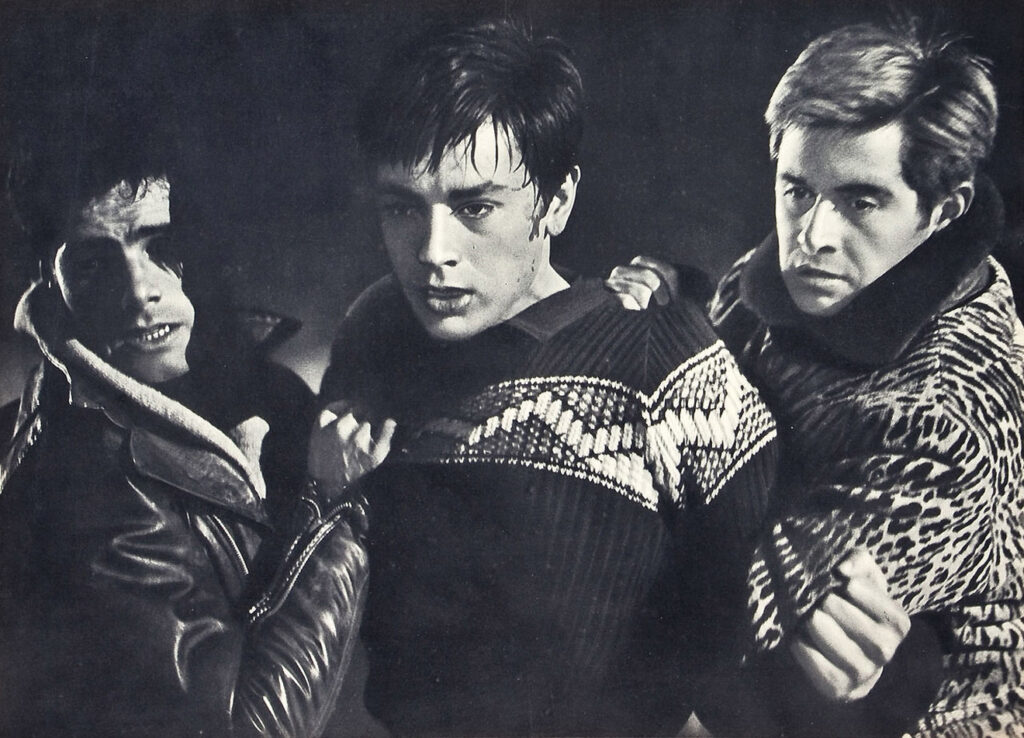

Rocco e i suoi fratelli (1960) may seem like a return to the subject of neorealism: an impoverished family from the Basilicata, Italy’s most disadvantaged region, moves to industrial Milan in search of a better life. However, this is only the background of a story that does not resemble the neorea leaf. The two brothers, the older Simone (Renato Salvatori) and the younger Rocco (Alain Delon), are in love with the same girl, the prostitute Nadia (Annie Girardo). Throughout the film, this plot triangle is turned to the viewer by various facets. At some points in the image of Rocco, Alesh Karamazov is clearly visible, and Simone looks like another brother – Mitya. Sometimes Rocco resembles Prince Myshkin, and Simon and Nadia – Parfen Rogozhin and Nastasia Filippovna from “Idiot”. The title of the film refers to the novel by Thomas Mann “Joseph and his brothers”, and the figure by Rocco refers to the old Joseph the Fair.

In “Rocco e i suoi fratelli” finally formed a trend that is clearly visible in the “La caduta degli dei”, – Visconti likes to tell several stories at once: some of them lead to the plot level, and some hide in reminiscences and references.

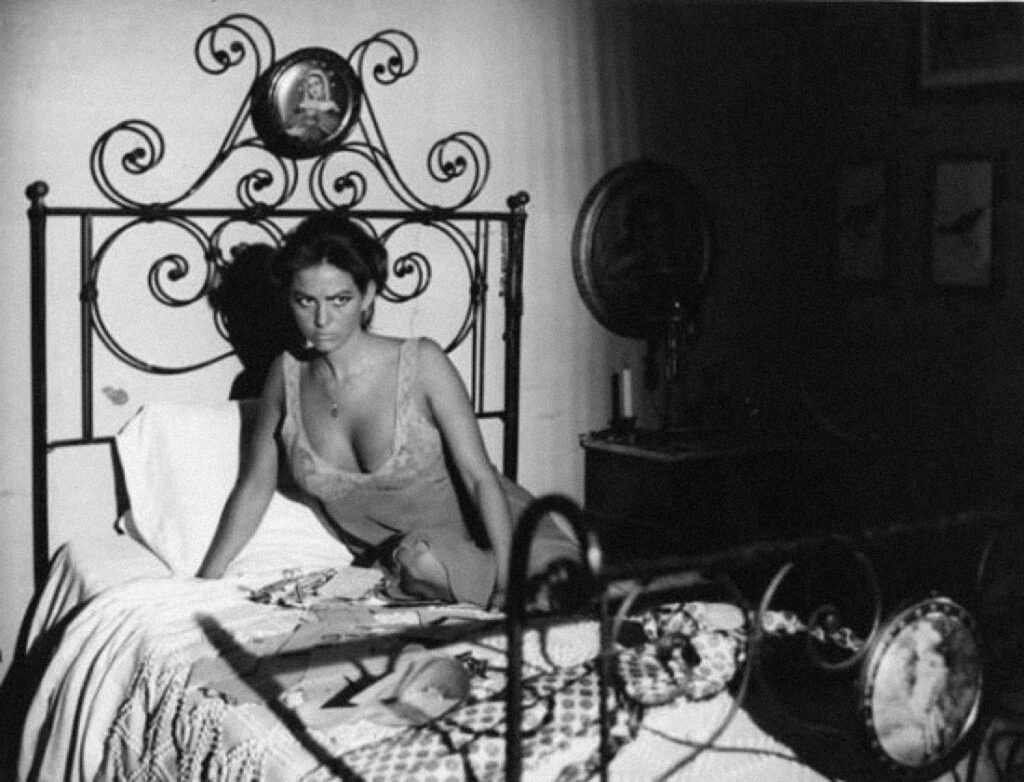

This is particularly evident in the film, which is worth watching in the footsteps – “Vaghe stelle dell’Orsa” (1965) . Claudia Cardinale is a young Italian girl named Sandra, who returned to her native Volterra with her American husband. Sandra hates her mother and misses her father, who died in Auschwitz. The ancient Greek myth of the Mycenaean princess Elektra, her mother Klitemestra and her father Agamemnon is guessed in this quite realistic story. The multi-layered storyline allows Visconti not only to refer to the stories of specific characters, but also to generalize them, to talk about the person as such – regardless of the time in which he lives, and his social situation.

Then you should return to a few years ago and watch the adaptation of Dostoevsky – “Le notti bianche” (1957) with Maria Shell, Marcello Mastroianni and Jean Mare. Visconti shifts the action from 19th century Petersburg to modern Livorno, uses the motif of sudden snowfall instead of white nights, makes a major change in the plot, but this does not prevent many literary scholars from considering the picture one of Dostoevsky’s best films in film history, because Visconti managed to keep the tone of the story.

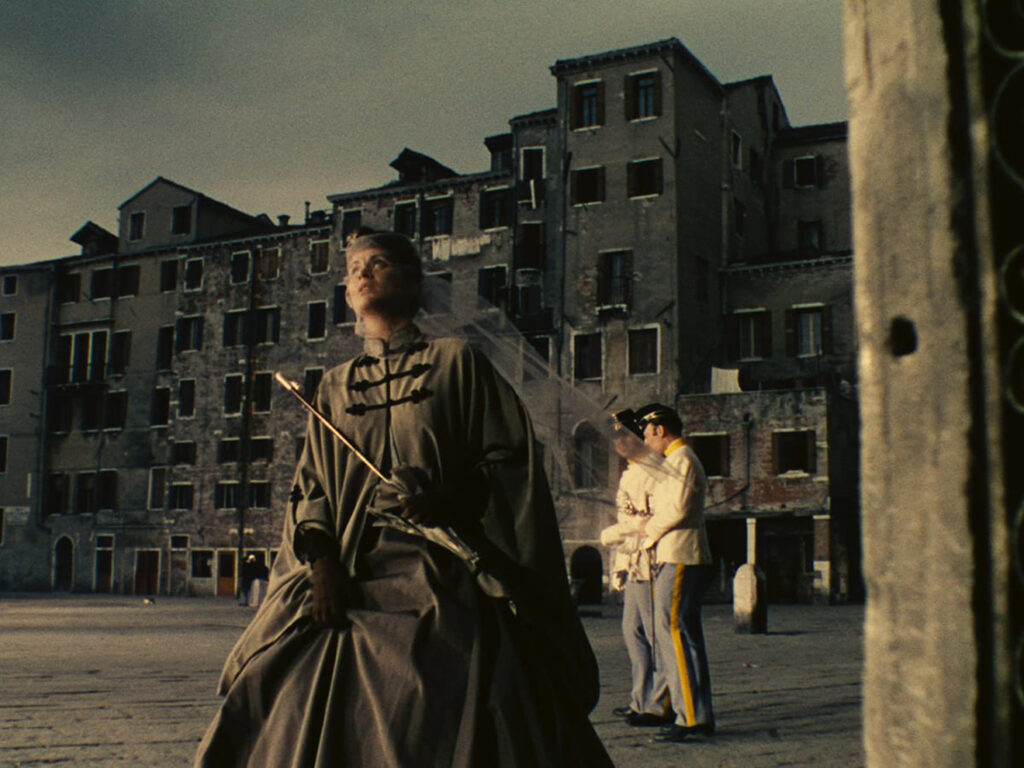

“Le notti bianche” is also called one of the best melodramas in Italian cinema. And then you can see another classic melodrama Visconti – “Senso” (1954). The director for the first time openly moved away from neorealism and turned towards the opera convention, filming a color costume film, which takes place in the era of Risorgimento .

Six of Visconti’s fourteen films are about history, and after “Senso”, two other historical works can be viewed. Together with “La caduta degli dei”, they constitute a “German trilogy”. In “Morte a Venezia” (1971) with Dirk Bogard and Björn Andresen Visconti combined the plot of the eponymous novel by Thomas Mann with the motives of the novel “Magic Mountain”, which dreamed to film. Visconti was the last great painter-historian and mythographer at the end of classical European culture. Like every sunset, this one is illuminated by flashes of tragic beauty, and Death in Venice” is one of its brightest flashes.

And finally you can see two paintings with autobiographical motifs – “Il gattopardo” (1963) and “Gruppo di famiglia in un interno” (1974). In both films, the lead role is played by American actor Burt Lancaster, who became a kind of alter ego director. In the first case it is a Sicilian aristocrat of the XIX century, observing the unification and democratisation of the country, in the second – a modern reclusive professor, not leaving his Roman apartment, but forced to admit young guests, noisy and restless. The orderly life of both of Lancaster’s heroes is invaded by a new world that they are interested in, but do not fully understand and accept. Like Visconti himself, they found themselves at the crossroads of time, but chose not a new but an old one.

The subject is taken from the homonymous novel by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa and the figure of the protagonist of the film, the Leopardopardo, is inspired by that of the great-grandfather of the author of the book, Prince Giulio Fabrizio Tomasi di Lampedusa, who was an important astronomer and who in literary fiction became Prince Fabrizio di Salina, and his family between 1860 and 1910, in Sicily (in Palermo and province and precisely in Ciminna and in the agrigento fief of Donnafugata, namely Ciminna, Palma di Montechiaro and Santa Margherita di Belice in the province of Agrigento).

The film won the Palme d’Or for Best Film at the 16th Cannes Film Festival.