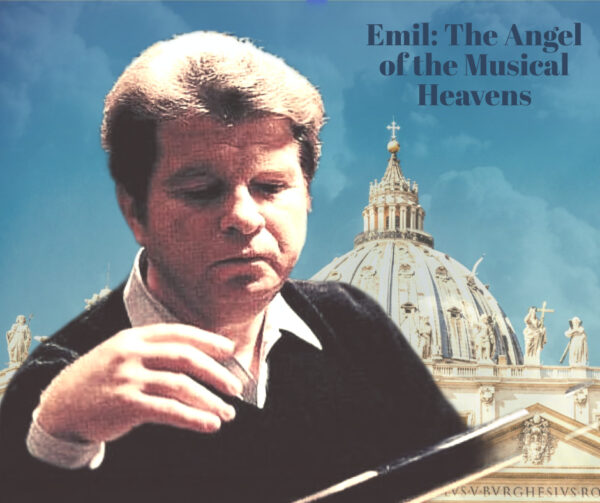

Emil Gilels had an extensive repertoire from different eras and styles. He performed both large-scale works with their philosophical depth and small forms with their wise simplicity. Gilels’s performances stood out with the deepest immersion in music. His playing was so inspired, as if the creation of the composition took place on stage. Gilels’s rhythm possessed the hypnotic power of influence. His power over musical time was unlimited.

In 1955, he became the first Soviet artist to tour the US since the 1920s, garnering rave reviews and even a citation in a Marianne Moore poem. He made his debut playing the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto in B flat minor with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Having won the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels in 1938, Gilels had been scheduled to perform the next year at the New York World’s Fair, of all places, but the outbreak of the war caused the trip to be cancelled…

The unforgettable feature of Gilels is lyrics. His piano is always soft, melodic, and always gives warmth “from heart to heart”. The sound of the pianist was astonishing. Throughout his life, he worked with the greatest tenacity and sought the shades of the color of the piano. The signature recording from the US tour is Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto with Fritz Reiner: “Dazzling in stratospheric Russian pianism, it’s an untrammelled powerhouse performance of visceral theatre, leonine attack, and flying fingers.” Following his first forays into the west as a flag bearer, Gilels’ style was maturing toward the richly inclusive intellectual lyricism he’s synonymous with today.

In 1955, as Toscanini was approaching his ninetieth birthday, Emil Gilels visited a great conductor before beginning his tour in the United States of America. “I knew Toscanini was going through the worst, most tragic phase of his life, says Gilels. There had been an irreparable misfortune. Toscanini, famous for his amazing memory, suddenly forgot the music at the concert. The orchestra stopped. The old maestro left the stage. The concert was interrupted. The press did not spare the musician. Newspapers began to write about the end of Toscanini, about the complete decline of his genius. Toscanini settled in a country house, not wanting to see anyone”. But for Gilels the old conductor made an exception. ” In the evening, in the dark, Gilels continues, we drove to an old house, which stood in a dense bush. I expected to see Toscanini, say a few words and leave”. That’s not what happened. Toscanini didn’t accept Gilels to show himself, but to listen to the music of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony together…

On September 12, 1985, Emil Gilels gave his last concert in Helsinki. A month later, on October 14, he died suddenly in Moscow. One of his last recordings of the B-minor prelude of Bach (аrr. А.Siloti) was a symbolic farewell to the audience of genius: so powerful in every sound is expressed the soul of the musician.

While Gilels’s place among the great pianists has never been in doubt, no other member of this chosen cohort has been so devoid of external charisma as this short, retiring man: not for him the magnetism of Horowitz, Michelangeli, or Richter. And yet, this golden-haired angel of music has surpassed anyone in the depth of the humanity of sound, in the strength of the musical will that drives any brilliant musical idea to the absolute.

During the World War II, the art of Emil Gilels inspired and called for victory. In the post-war period, the pianist expected endless triumphs in Paris, Prague and Rome, in Germany and England, in the USA and Mexico, Canada and Japan. He has performed with the most celebrated conductors and orchestras in the world; his records entered the homes of millions of people.

At the age of 16, Gilels took part in the First Competition of Performing Musicians (Soviet Union). The success of the young man was a complete surprise for him. One of Gilels’s biographers wrote: “The appearance of a gloomy young man on the stage went unnoticed. He busily approached the piano, raised his hands, hesitated, and, stubbornly pursing his lips, began to play. The hall became alert. It became so quiet that it seemed people froze in immobility. Eyes rushed to the stage. And from there came a powerful current, capturing the listeners and forcing them to obey the performer. The tension grew. It was impossible to resist this force, and after the final sounds, everyone rushed to the stage. The rules were violated. The listeners applauded. The jury applauded. And only one person stood imperturbably and calmly, although everything worried him – it was the performer himself. Having unconditionally won the competition, Gilels became famous throughout the country.” In 1935, Emil Gilels graduated from the conservatory and entered the school of higher skill at the Moscow Conservatory, where Heinrich Neuhaus became its leader. In 1936, Gilels received second prize at a piano competition in Vienna.

Gilels’ whole life is work. Every minute of it is devoted to music. Emil’s attitude to music was special: he was a devoted knight of art, which was the shrine of his life. He wanted to study all piano literature, to study the soul of every composer. Gilels went up all the steps of the pedagogical ladder from an assistant in the class of G. Neuhaus to a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. He brought up many talented pianists, for many years he headed the pianistic jury of the International Tchaikovsky Competition.

Here’s a short excerpt of a New York Times article that came out after the death of a legendary musician

Emil Gilels, one of the world’s great pianists and, in 1955, the first Soviet musician to perform in the United States since Sergei Prokofiev in 1921, died in a Moscow hospital Monday, apparently of kidney failure. Mr. Gilels also had a history of heart trouble, and the exact cause of death was not reported. He was 68 years old, and had been scheduled to embark on a concert tour of Switzerland next week.

Mr. Gilels was a stocky man with a shock of sandy hair and short, stubby fingers, uncharacteristic for a pianist. But his greatness was widely recognised. Howard Taubman of The New York Times proclaimed him a ”great pianist” on the occasion of his New York debut at Carnegie Hall on Oct. 4, 1955. After his first New York recital a week later, Harold C. Schonberg invoked the phrase ”little giant,” the term the critic W. J. Henderson had used for the pianist and composer Eugen d’Albert at the turn of the century.

Mr. Gilels continued to receive such encomiums throughout his career, both in the Soviet Union, where he had taught at the Moscow Conservatory since 1938, and in the West. Altogether, he made 14 American tours, the last in 1983. On the occasion of his last New York recital, on April 16, 1983, Donald Henahan wrote in The Times of his ”formidable, high-finish technique and beautiful control of nuance.”

…Basically, however, Mr. Gilels was a big, rich-toned pianist who could ride triumphantly over an orchestra in the mainstream Romantic piano concertos – those of Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt, Brahms and Tchaikovsky, all of which he recorded. He wasn’t always note-perfect, but he commanded his repertory with an elan that made such flaws seem insignificant. And unlike some powerhouse virtuosos, he had a poetic gift that enlivened slow movements…

…His American debut in 1955 was preceded by several European engagements, starting in Italy in 1951. The first American tour, at the height of the Cold War, was made possible by the surge of good feeling following the Geneva Conference, and by the efforts of the violinist Yehudi Menuhin in obtaining American visas for Mr. Gilels and Mr. Oistrakh…

…A hearty, straightforward man, Mr. Gilels always professed pleasure in his warm reception by American audiences. ”I first came here 22 years ago,” he said in 1977. ”I lost here in the United States very much of my heart. You know, I left here a good portion of my life.”

Survivors include a daughter, Elena, who is herself a successful concert pianist. A Moscow Conservatory spokesman said yesterday that a memorial ceremony would be held tomorrow at the conservatory, and that Mr. Gilels would be buried the same day.