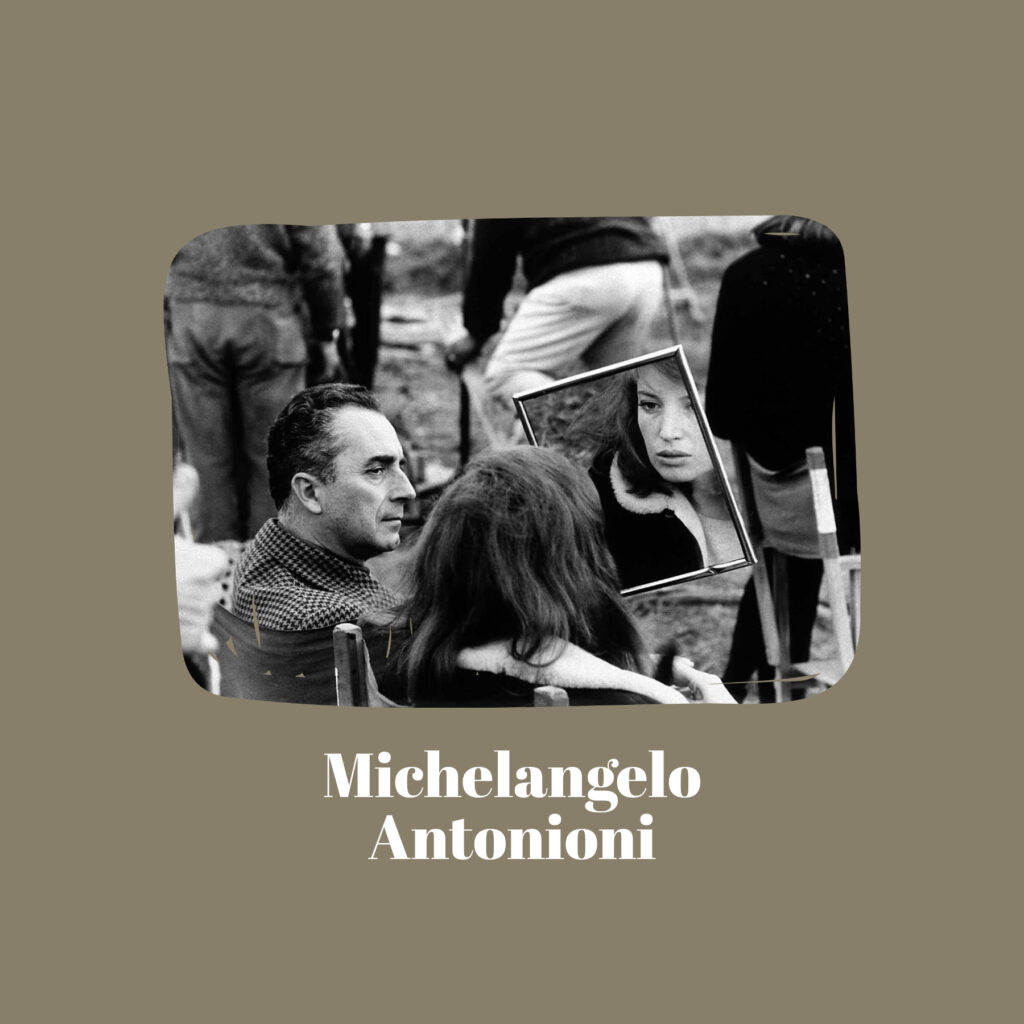

At over forty years old, Michelangelo Antonioni made his feature film debut with Cronaca di un amore (1950), a movie that already included elements that would later come to characterize his style: psychological analysis, the topic of the bourgeoisie’s crisis. In I vinti (1952), interest in the inner life comes back with an overwhelming intensity. Also in the following films, the director continues to give priority to feelings and moods: in La signora senza camelie (1953), a restless portrait of a woman, shows how the love feeling can change and/or dissolve, while in the episode of L’amore in città (1953) makes the protagonists talk about some attempted suicides for love. In Le amiche (1955), based on Cesare Pavese’s novel Tre donne sole, at a certain point, Clelia leads Carlo into the squalid suburbs of Turin that saw her born and a peeling wall. Il grido (1957) – said Antonioni himself – was born looking at that wall: Aldo, the worker protagonist of the 1957 film is the continuation of Carlo di Le amiche, who has lost Clelia forever and cannot understand the reason. Changing the social connotation, the problems related to feelings remain: certain issues are not specific to the bourgeoisie and Il grido, although the environment has changed, follows the same line as previous films. It concludes a first phase of the production of Antonioni and begins the so-called cycle of alienated affections.

L’avventura (1960), La notte (1961), L’eclisse (1962), Il deserto rosso (1964), more than a tetralogy, constitute a real unitary creation: the desperate need of Claudia, Lidia, Vittoria and Giuliana, different names for the same woman, to fill the inner abyss, to overcome the anguish with a relationship of authentic love, collides, inexorably, with frustration. – There are days when holding a cloth, a needle, a book, a man, is the same thing – says Victoria in L’eclisse, definitively sanctioning the incommunicability between the sexes. Antonioni’s research does not end, however, here: the crisis of meaning not only affects feelings but even the facts and individual identity, as demonstrated by the events of the photographer of Blow Up (1966), who believes he sees and does not see, and the journalist of Professione: reporter (1974) who, before the exchange, once, was another. Between the two films mentioned above stands, along with Chung Kuo. Cina (1972), Zabriskie Point (1970), with the famous sequence of the explosion of the symbols of well-being, shot in slow motion with 17 cameras, to music by Pink Floyd. The director brings to completion, in this way, the criticism, present in all his works, to a certain type of society and model of development.

If for the 1964 film, wanting to make the shades of anguish, Antonioni paints antinaturalistically objects and environments, with Il mistero di Oberwald (1980), takes another step forward and replaces the paint with electronics, certainly not to get results from “special effects”, at Coppola, but to further enrich the epiphanic structure of his works. Although no blow-up really captures the events and although the mysteries of the sun seem to Nicholas of Identificazione di una donna (1982) more affordable than those of human nature, Antonioni continues stubbornly to look, as stated in the title of one of his films, Al di là delle nuvole (1995), obsessed with the true image of that absolute, mysterious reality that no one will ever see. It is no coincidence then that he decides, for his latest documentary film, Lo sguardo di Michelangelo (2004), to stand in front of Michelangelo Buonarroti’s Mosè and tell that masterpiece. Even the artist of the sixteenth century dug the marble to find the last layer, removed, removed, until you get where the marble becomes transparent: just like Antonioni who, with his films, is approaching the decomposition of any image, any reality. In both cases, the images pose a question, not purely cognitive, aesthetic, but moral: Corrado di Il deserto rosso responds, significantly, to Giuliana – You say: What should I look at? I say, how do I live?