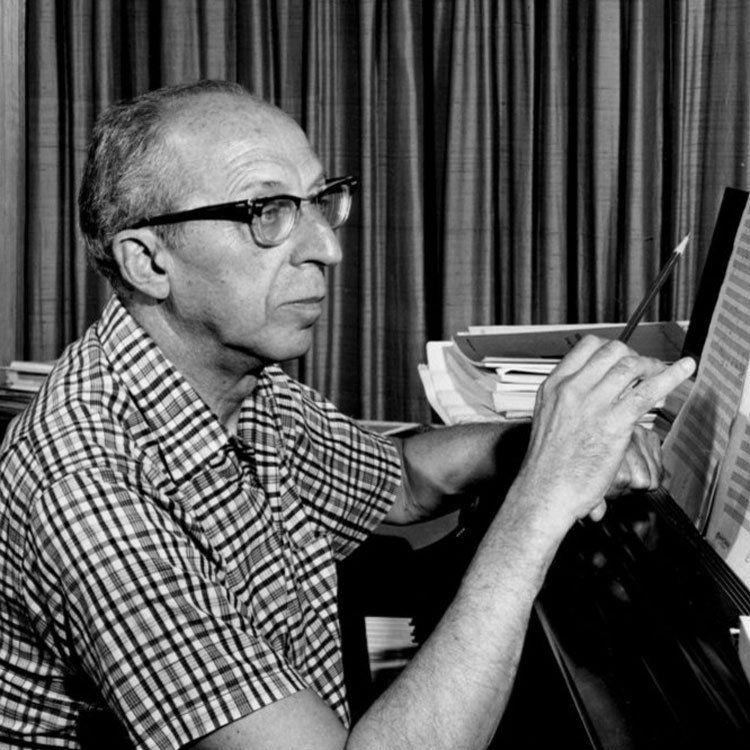

“I don’t think the Symphonic Ode has been properly appreciated yet. Personally I think it’s one of my best works. I’d have liked to conduct it here this trip, but it needs too much rehearsal time,” – Aaron Copland said in an interview for the Guardian in 1960. History of Culture recalls whether there were any his works that Aaron Copland felt did not receive recognition enough.”

Between the creation of the symphony ode in 1929 and its revision for the 75th season of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, 36 years passed. It is felt that the composer has on several occasions in his creative quest returned to this work. He hoped to give the work a new start. Copland created the Ode in 1929, as critics say, in his “abstract” period “after the jazz phase”.

Copland wrote then important instrumental works in a style that he himself calls “severe” (the Piano Variations, Short Symphony, Statements). This lasted until about 1935, when he began working simultaneously in two styles – a “popular” one, based on less aggressively popular material than that of the jazz period (El Salon Mexico, the ballets “Billy the Kid,” “Rodeo,” “Appalachian Spring,” the opera “The Tender Land,” and many film scores), the other a more “personal” style, less tough and more lyrical than that of the “abstract” period (Piano Sonata, Violin Sonata, Third Symphony, Piano Quartet, Piano Fantasy).

Recall that the 1920s were formative for Copland: then, under the guidance of Nadia Boulanger, the composer studied the works of J.S. Bach and his predecessors. He also devoted himself quite a bit to the contemporary music of the time. Paris, and even all of Europe, became a new ground for inspiration, and he grew his fruits on it, studying a huge musical material: from the performances of vocal music of the Renaissance to the latest premieres of new works, including even the most daring of modern composers who preached general “release from dissonance.” It was from this mix that the young composer emerged on the international music scene in the 1920s.

Copland produced the Symphony Ode as his first major work exclusively for orchestra. In a sense, this is one of his least characteristic works, certainly one of the composer’s most conscious compositions on the face. According to American composer John Adams, the young Copland was “in the minds of the polite audiences of the BSO… a hooligan.” The 1955 revision reduced the size of the orchestra and softened Ode’s harsh mood a bit.

Writers and musicians try to discover the programmatic nature of the work, as a kind of “musical urban landscape” or “the urban tone of the poem.” Copland answers this question clearly: “The title Symphonic Ode is not meant to imply connection with a literary idea,” wrote the composer. “It is not an ode to anything in particular, but rather a spirit that is to be found in the music itself.”

The ode begins with a dark brass statement, followed by a very short string motif that is both blues, jazz and faintly Eastern European Jews. These ideas become practically the twisting and weaving of the whole piece, the virtual motif of New York, penetrating through modifications and variations throughout this continuous five-section work.

The outer sections are musically similar to the hustle and bustle of a big city, while the quieter inner sections are reminiscent of the surreal stillness of the urban landscape at 3:00 a.m. sheer abundance and rhythm, and, as composer Adams noted, “lean, spare, clean sense of space.”