Long before “Halloween” and the “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” a recognized Suspense master could have shot something horribly shocking. If Hitchcock had succeeded, the history of cinema would have added another masterpiece, breaking every taboo possible.

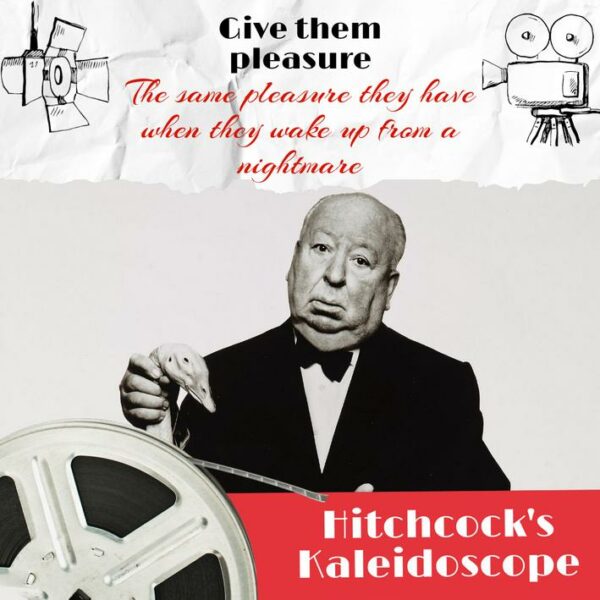

Of all Alfred Hitchcock’s phenomenal achievements in the thriller film industry, the “Psycho” is the scene where a man dressed in his late mother’s dress kills a naked woman in the shower of a motel. But Hitchcock planned to make an even more shocking film. This could be “Kaleidoscope”.

But it didn’t happen. The future “Kaleidoscope” was considered so scandalous that even a man who was already famous for his “Psycho” was not allowed to film it.

Back in 1964, Hitchcock registered with the Writers Guild the idea of a film inspired by the story of two English serial killers from the 1940s, Neville Heath and John Hay. This may have been a prequel to his 1943 psychological thriller “Shadow of a Doubt ” in which Joseph Cotten played the Merry Widow murderer. How he killed widows and if they were happy about it, we don’t see it in that movie. But Hitchcock believed that in the more tolerant ’60s he could afford more – not only to show how a serial killer seduces and kills his victims, but to make him the protagonist of the story.

The director asked the American writer Robert Bloch (the author of the novel “Psycho”, on which the eponymous film was made) to write the novel on the basis of his new idea, and then recycle it into a script. As they say, in 1964 Bloch considered the idea too “disturbing”. But when Hitchcock asked his old friend Benn W. Levy to write the script in 1966, he didn’t hesitate.

He said that one of the seduction scenes “should become the most chilling blood in the history of cinema” and the police chase should be filmed not from the point of view of the persecutors, but from the point of view of the persecuted. However, Hitchcock went even further. He wrote his script sketch for the first time since he did it in 1947 for “The Paradine Case”.

The action must take place in New York City. The monster in Hitchcock’s script is a cute mama’s boy named Willie Cooper. His desire to kill is awakened by the proximity of water. Three key scenes occur near water: at the waterfall where he kills a UN employee, on a rusty ship in a dock, and at an oil refinery where his victim is a police detective who risks her life to catch a murderer.

Hitchcock could have shot something that was disgusting. Here’s what he wrote in his screenplay: “THE CAMERA HITS A GIRL’S BELLY, WE SEE THE BLOOD STREAMS”. And that wasn’t all. In his room, Willie kept a bunch of bodybuilder magazines (a hint that he was gay), and one day his mother had to catch him masturbating. Many nude scenes were to be filmed in New York City, with half-naked models taking part.

Even Truffaut was concerned. After reading the script, he wrote to Hitchcock about his doubts. Truffaut, however, did not want to interfere with the master’s affairs. “It does not worry me too much because I know that you shoot such scenes with real dramatic power, and you never dwell on unnecessary detail,” he wrote.

But the film was never meant to be Hitchcock’s typical product. He was going to experiment – recruit unknown actors, use hand-held cameras, natural light, and live-action footage. In short, anything to prove it: it is not tired and not worked out. He hired two other writers, Hugh Wheeler and Howard Fast, to polish his sketches. The latter then shared his memories of that time in the book written by Patrick McGilligan, “Alfred Hitchcock: Life in Darkness and Light”. “Jesus, Howard, said Hitchcock to Fast. I just saw Antonioni’s “The Blow-Up”. These Italian technical directors are a century ahead of me! What have I been doing all this time?”

Unfortunately, the management of MCA/Universal did not share Hitchcock’s enthusiasm. He came to a meeting with the bosses, armed with a bunch of photos, samples taken, and a detailed scenario including a description of 450 positions for the camera. As John William Law characterized in “The Lost Hitchcocks: Uncovering the Lost Films of Alfred Hitchcock”, Hitchcock has moved on this project much further and deeper than anyone else in any unfinished film. But it was all for nothing. They very quickly rejected the script and told Hitchcock that they would not let him shoot this.

Raymond Foery, author of the book “Alfred Hitchcock’s Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece,” blames Lewis Robert “Lew” Wasserman, owner of the studio.

Wasserman had known Hitchcock since the late ’40s and was his agent for a while. But he wanted Universal to get rid of the reputation of producing base horror films. And this project seemed to him to be too base and did not meet his ideas about what Hitchcock should shoot.

Whatever the reasons for the rejection, Hitchcock was confused. They cut off his attempt to do exactly what they had previously called him to do, To do something completely different, to keep up with the times.

Some of his ideas and concepts somehow slipped into the 1972 film “Frenzy”, a picture of a serial killer – no first-rate actors, with a terrible scene of rape and murder.

But “Frenzy,” where the action takes place in London, looks quite traditional compared to what Hitchcock planned in “Kaleidoscope”.

And by then, American cinema had already embraced the innovations of the European new wave, so Hitchcock had missed the chance to show Hollywood what an avant-garde he could be.