It would be impossible to talk about the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century in art and music without mentioning some significant events and works. It was a time of intense growth of new ideological and artistic views: movements from late Romanticism to stylistic polyphony of the 20th century. The moment when the last flowers of the late Romanticism flashed with the most vivid colors, the works most fully and saturated manifested the properties of the passing time.

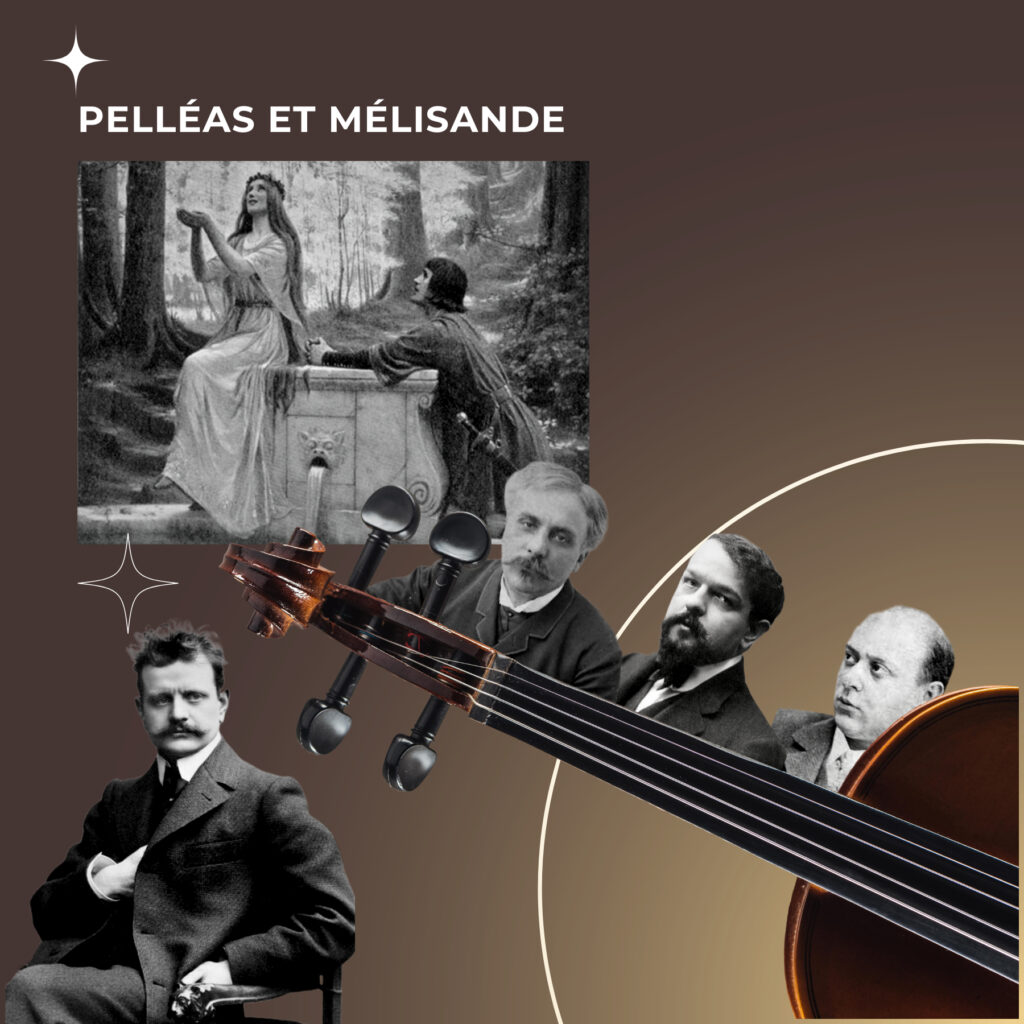

One of the amazing dialogues with bygone era in music was the plot of the play by Maurice Maeterlinck “Pelléas et Mélisande”. The play, published in 1892, stands fifth in the chronological order of his dramatic works. It was preceded by “La Princesse Maleine” (1889); “L’Intruse, Les Aveugle”s (1890); and “Les sept Princesses” (1891). “Pelléas et Mélisande”, dedicated to Octave Mirbeau “in token of deep friendship, admiration, and gratitude,” was first performed on May 17, 1893.

“Take care,” warns The Old Man in that most simply touching of Maeterlinck’s plays, Intérieur; “we do not know how far the soul extends about men.” It is a subtle and characteristic saying, and it might have been used by the dramatist as a motto for his “Pelléas et Mélisande”; for not only does it embody the central thought of this poignant masque of passion and destiny, but it summarizes Maeterlinck’s attitude as a writer of drama.

“In the theatre,” he says in the introduction to his translation of Ruysbroeck’s l’Ornement des Noces Spirituelles, “I wish to study … man, not relatively to other people, not in his relations to others or to himself; but, after sketching the ordinary facts of passion, to look at his attitude in presence of eternity and mystery, to attempt to unveil the eternal nature hidden under the accidental characteristics of the lover, father, husband…. Is the thought an exact picture of that something which produced it? Is it not rather a shadow of some struggle, similar to that of Jacob with the Angel?” Art, he has said, “is a temporary mask, under which the unknown without a face puzzles us. It is the substance of eternity, introduced …by a distillation of infinity. It is the honey of eternity, taken from a flower of eternity.” Everywhere, throughout his most deeply characteristic work, he emphasizes this thought—he would have us realize that we are the unconscious protagonists of an overshadowing, vast, and august drama whose significance and dénouement we do not and cannot know, but of which mysterious intimations are constantly to be perceived and felt. The characters in his plays live, as the old king, Arkël, says in “Pelléas et Mélisande”, like persons “whispering about a closed room,” This drama – at once his most typical, moving, and beautiful performance – swims in an atmosphere of portent and bodement; here, as Pater noted in the work of a wholly different order of artist, “the storm is always brooding;” here, too, “in a sudden tremor of an aged voice, in the tacit observance of a day,” we become “aware suddenly of the great stream of human tears falling always through the shadows of the world.”

Mystery and sorrow – these are its keynotes; separately or in consonance, they are sounded from beginning to end of this strange and muted tragedy. It is full of a quality of emotion, of beauty, which is as “a touch from behind a curtain,” issuing from a background vague and illimitable. One is aware of vast and inscrutable forces, working in silence and indirection, which somehow control and direct the shadowy figures who move dimly, with grave and wistful pathos, through a no less shadowy pageant of griefs and ecstasies and fatalities. They are little more than the instruments of a mysterious will, these vague and mist-enwrapped personages, who seem always to be unconscious actors in some secret and hidden drama whose progress is concealed behind the tangible drama of passionate and tragic circumstance in which they are ostensibly taking part.

The premiere of “Pelleas et Melisande” took place at the Bouffes-Parisiens under the direction of Lugné-Poe. He, perhaps inspired by The Nabis, an avant-garde group of symbolist artists, used very little light on the stage. He also removed the ramps. He put a gauze veil on the stage, giving the performance a fabulous and otherworldly effect. It was the opposite of realism, popular at the time in the French theater.

Maeterlinck was so nervous on the night of the premiere that he did not come. Critics laughed at the performance, but Maeterlinck’s colleagues took it more positively. Octave Mirbeau, to whom Maeterlinck dedicated his play, was impressed by the work that stimulated a new direction in stage design and theatrical performance.

With the play of Maeterlinck, the history of music turned a new and surprising page. The masterpiece provided the basis for a number of musical works.

In 1898, Gabriel Fauré wrote the music for the play and asked Charles Koechlin to orchestrate it. Later, Fauré created the suite based on his music. Perhaps the most famous from musical works on “Pelléas et Melisande” is the Claude Debussy’s opera (1902) with the same name. The play inspired amazing Arnold Schoenberg’s early symphonic poem of 1902-03. Jean Sibelius also wrote the orchestral suite Pelléas et Melisande, or. 46, in 1905. In 2013, Alexander Desplat composed the Sinfonia Concertante for flute with orchestra, inspired by Maeterlinck’s masterpiece.

Fauré’s suite Pelléas and Melisande, op. 80, has created from the incidental music for the play’s first English language production in London.

The score was ordered in 1898 by Mrs Patrick Campbell for the first production of the play in English, in which she played Johnston Forbes-Robertson and John Martin-Harvey. Mrs Campbell invited Debussy to compose the music, but he was busy working on his opera version of Meterlink’s play and declined the invitation. Debussy wrote: “J’aimerai toujours mieux une selected où, en quelque sorte, l’action sera sacrifiée à l’expression longuement poursuivie des sentiments de l’âme. Il me semble que là, la musique peut se faire plus humaine, plus vécue, que l’on peut creuser et raffiner les moyens d’expression.”

Later, Fauré accepted a commission to write incidental music. The composer worked under a great time constraint. In a letter to his wife, he wrote: “I will have to grind away hard for Mélisande when I get back. I hardly have a month and a half to write all that music. True, some of it is already in my thick head!”

To keep the tight production schedule, Fauré reused some of the earlier unfinished music and enlisted the help of his pupil Charles Koechlin, who orchestrated the music. Later, Fauré created a suite of four pieces.

Fauré recycled previously written music, most notably the famous Sicilienne, which may have been conceived originally for the incidental music of Moliére’s Le Bourgeois gentilhomme. He relied on his student, Charles Koechlin, to provide the orchestrations for the small theater ensemble. Later, Fauré returned to the music and provided his own orchestrations for the concert suite.

Fauré’s music is elegant, serene, and magical. The Prélude (Quasi Adagio) is filled with both sensuality and tragic foreboding. Pastel colors emerge as the flute and other wind instruments blend with the strings. A series of instrumental voices, including the solo flute, oboe, clarinet, and cello take the stage in a shimmering musical drama. In the Prélude’s final moments, a horn call echoes through the forest.

The second movement, Fileuse (Andantino quasi Allegretto) is a “spinning song.” A pastoral melody in the oboe rises above incessant triplets in the violins which depict Mélisande at a spinning wheel. A dialogue emerges between the oboe and bassoon, while the clarinet initiates one of the score’s recurring themes.

The Sicilienne (Allegretto molto moderato) is one of Fauré’s most beloved pieces. Introduced by the flute and harp, its buoyant melody begins in veiled G minor, flirts with major, and breaks into the sunlight at its final cadence. In the context of the play, this flowing music is evocative of the water fountain in which Mélisande loses her wedding ring. It accompanies the blissful meeting of Pelléas and Mélisande.

The Suite concludes with The Death of Mélisande (Molto Adagio). Set in the melancholy key of D minor with modal inflections, it is a solemn funeral procession. The flute is heard in its haunting lowest register amid a quiet trumpet call and plodding timpani drumbeats. The final bars drift away into eternal lament.

Fauré conducted the orchestra at the premiere of the Prince of Wales Theatre on 21 June 1898. Campbell was fascinated by his music, in which, as she wrote, «he took with tender inspiration the poetic purity that permeates and envelops the beautiful Meterlink’s play».

There are two different versions of the original theatrical score «Pelléas and Melisanda». The first is Koechlin’s autograph of the orchestral score, dated May and June 1898, which includes several sketches by Faure in a short score. The second is the score of conducting Fauré in London; it is also a manuscript written in Koechlin’s handwriting.

Fauré later reused the music for Melisanda’s song in his “La chanson d’Ève”, adapting it to the words of the symbolist poet Charles Van Lerberghe.

Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, drame lyrique en 5 actes et 12 tableaux, was performed for the first time at the Opéra-Comique stage, Paris, April 30, 1902. Its first performance outside of Paris was at the Théâtre de la Monnaie, Brussels, January 9, 1907; its second was at Frankfort, April 19, 1907. Its third will be the coming production at the Manhattan Opera House, New York. The original Paris cast was as follows: Pelléas, M. Jean Périer; Mélisande, Miss Mary Garden; Arkël, M. Vieuille; Golaud, M. Dufrane; Geneviève, Mlle. Gerville-Réache; Le petit Yniold, M. Blondin; Un Médicin, M. Viguié. M. André Messager was the conductor. The work was admirably mounted under the supervision of the Director of the Opéra-Comique, M. Albert Carré.

Debussy worked on the opera for ten years (from 1892 to 1902). After the opera was staged, the composer wrote to the General Secretary of the Opéra stating that «for a long time I have tried to write music for the theater, but the form in which I wanted to put it was so little familiar that after a few experiments I almost gave up».

“The “Palleas” drama, which, despite its fantasy atmosphere, contains much more humanity than the so-called “life documents”, seems to me remarkably consistent with what I wanted to do. There is an expressive language that can be absorbed into music and orchestral attire.”

Claude Debussy

In July 1893, the composer, with the assistance of the writer Henri de Rainier, asked Maeterlinck to consent to the use of his drama for the opera libretto (a letter from the playwright to Rainier dated 8 August 1893). The composer is departing for Belgian Ghent in November. He obtained permission from the minor Maeterlinck to use his drama as a basis for the opera. Debussy mostly finished work at August 17, 1895 (first edition).

The Paris Opera Comique commissioned the opera in 1901. At this time, Debussy and Maeterlinck had a scandalous break, apparently due to the playwright’s desire to assign the role of Melisanda to the singer Georgette Leblanc, who had performed successfully on stage at the Comedic Opera House and was his lover. In Leblanc’s memoirs, it is claimed that the composer initially endorsed Maeterlinck’s terms and even had multiple rehearsals with the singer. Albert Carre, director of the Opera-Comique Theatre, proposed and insisted on an invitation to play the role of Melisanda by young singer Mary Garden, with success in the title role in the famous opera G, Charpentier «Louise». Debussy agreed to give the Scottish singer the role of the heroine in his opera after hearing her sing on January 13, 1902.

On 14 April 1902, Maeterlinck published an open letter in the newspaper «Figaro» in which he announced that «Pelleias» had become foreign to him and almost hostile, about the violation of his copyright, the premiere of the opera is preparing against his consent and opinion, his proposed performer is replaced by another and the text makes arbitrary and absurd bills and distortions. Maeterlinck concluded his letter stating that he wished Debussy’s opera a «quick and loud» failure. The playwright is said to have even trained in pistol shooting, intending to kill Debussy. The instrumentation and final finishing of the score continued until the last days before the premiere. The work of the composer did not stop after the production of the opera – he repeatedly returned to the score and improved it.

Schönberg’s and Debussy’s “Pelleas” are almost the same age, although the way of feeling and reliving the symbolism of Maeterlinck’s poetry is different. Moreover, in a paper published many years later, Schönberg clarifies the genesis of his poem in these terms: “At first I had planned to make Pelleas und Melisande a play, but then I gave it up even though I didn’t know that Debussy was working on his opera at the same time. I still regret not having realized the original project. My work would have been different from that of Debussy: maybe I would not have caught the wonderful scent of poetry, but I would have made the characters more singable. On the other hand, the symphonic poem was useful to me because it taught me to express moods and characters in well-formulated musical units, a technique that a play would perhaps not have favored as well”.

Maeterlinck’s play had a significant meaning in Schönberg’s work. It became one of the starting points for a change in his musical style and one of the compositions summarizing his early period. Schönberg wrote symphonic poem for orchestra “Pelleas and Melisande”, op. 5, in 1903, but it was still more than 15 years before the definitive domination of dodecaphone music was finally established, but this music was already resentful to critics and the public.

It is true that in the Schönberg’s “Pelleas” there are reminiscences of late-Romantic music, with obvious references to Wagner, Brahms, Richard Strauss and Reger, as for counterpoint, but, as the author himself claims, In this poem there is a new type of harmonies that preludes the successive conquests of twelve-tone composition. Only four years later, in 1906, precisely the anticipatory discoveries of the “Pelleas” became the centre and the determining nucleus of the Chamber Symphony no. 1, op. 9, initiating those counterpoint procedures that are the basis of the method to compose with twelve sounds.

The value of the Schoenberghian poem must be understood both in the historical location of this music and in the intense expressionistic power contained in the orchestral discourse, conducted with strong creative incisiveness in trying to overcome the heavy Wagnerian legacy. And in the accentuated contrast and timbral exasperation of the instrumentation lies perhaps the greatest value of this page, whose orchestral ensemble is very wide and includes 1 piccolo, 3 flutes, 3 oboes, 1 English horn, 4 clarinets, 1 bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, 1 controfagotto, 8 horns, 4 trumpets, 6 trombones and bass tuba, timpani, percussion instruments, glockenspiel, two harps and strings.

In December 1901 Schönberg left Vienna and moved to Berlin, where the writer Ernst von Wolzogen had invited him as conductor to the “Oberbrettl”, a literary cabaret in grand style that gave its performances at the Buntes Theater (Color Theatre) and who had become, under the guidance of Wolzogen, a meeting place of the artistic avant-gardes of the time. In April 1902, through Wolzogen Schönberg, he came into contact with Richard Strauss, who, in addition to providing him with a teaching post at the Stern Conservatory and a scholarship from the Liszt Foundation, had undertaken to support him in his work as a composer.

Strauss was convinced that the full affirmation of a musician could not be separated from the theatre, as he too was experimenting. It was with this conviction that he suggested that Schönberg consider the play Pelléas et Mélisande by Maurice Maeterlinck as an opera project (in his opinion excellent, but obviously not so much to devote himself to it), performed in Paris in 1893 and immediately became the opera-manifesto of the symbolist theater.

Begun on 4 July 1902, the composition was completed in Berlin on 28 February 1903. The first performance took place, under the direction of the author, in Vienna (where Schönberg had meanwhile returned) on January 26, 1905, causing great riots among the public and even among critics. Not only the exorbitant length of the work (three quarters of an hour: not even Strauss had yet reached this point) and the enormity of the staff, including 17 woods, 18 brass instruments, two harps and 64 strings as well as a large percussion (Mahler’s great Symphonies were not yet at home in Vienna), but also the aggressiveness of the writing and the unprecedented counterpoint density, pushed to the limits of tonal indeterminacy.

The lack of rehearsals also contributed to the failure (in the same concert the first performance of Zemlinsky’s Die Seejungfrau orchestral fantasy, conducted by the author, was planned) and Schönberg’s lack of familiarity, as conductor, with the masses. This is demonstrated by the fact that only six years later, under the direction of Oskar Fried, the piece had a positive reception and, unlike other works by Schönberg, it was no longer a problem either for orchestras or for listeners. It may be added as a curiosity that in an introduction to the score of December 1949 Schönberg still recalled the particularly malicious judgment of a critic, Not named, who after listening had suggested to put him in the asylum and keep the music paper out of his reach.

That critic was actually Richard Strauss, who in a letter to Alma Mahler a few years after the first performance had expressed himself in these terms: “Today, the only way to help Schönberg would be to lock him in an asylum. Rather than doodling pentagram paper, you’d better shovel snow”. Schönberg had commented: “From the artistic point of view, he [Strauss] today does not interest me at all, and what I had learned from him at the time, thank God I misinterpreted”.

If the score of Schönberg had marked the moment of maximum approach to Strauss, on the other hand he detached himself in the way of interpreting the function of music in the poem for orchestra: saving in relation to the inspiring drama the autonomy of the symphonic form. But even of this outcome the author was satisfied only in part, especially after the evolution of his art had taken him in all other directions: while recognizing that in the work of youth appeared “many traits that helped form the style of my maturity”he considered it an outdated passage. ” The symphonic poem Pelleas und Melisande”, he wrote in the recalled introduction of 1949,

“is inspired from the beginning to the splendid drama of Maurice Maeterlinck, of which I have tried to reflect every detail with only a few omissions and with slight changes in the sequence of scenes. Perhaps, as often happens in music, more space is reserved for love scenes”.

Arnold Schönberg

Schönberg continued by exemplifying the musical themes that represented, “on the type of Wagner’s Leitmotifs”, the three main characters of Melisande, Golaud and Pelleas, and enumerating the transformations that corresponded to changes in atmosphere and plot developments. What he wanted to emphasize above all was the novelty of unusual solutions both in melody and harmony (“many melodies contain extra-tonal intervals, requiring unusual movements of harmony”) and the richness of the instrumentation: almost with complacency lingered on the scene in which Melisande hangs her hair out of the window (“the relative passage begins with flutes and clarinets that imitate each other strictly. Harps are added, while the solo violin plays Melisande’s tune and the cello only Pelleas’s theme.

Then continue the violins divided in the high register and the harps”), then on the one in which Golaud accompanies Pelleas in the terrifying underground secret, when “a remarkable sound is produced from many points of view but especially because here for the first time in the musical literature is used a largely unknown effect: the glissando of trombones”. The feverish tension that thickens in the polyphonic lines determines a harmonic writing of extraordinary, restless mobility: the piece is implanted in D minor (this tonality, dear to the young Schönberg, is also found in Verklärte Nacht op. 4 and in the first String Quartet op. 7: it is also the basis of the Gurrelieder, then already composed but completed in the instrumentation much later, making in every sense treasure of the experience of the symphonic poem). However, the harmonic boundaries are very wide and touch extreme zones of tonal uncertainty: there are also used chords for quarts and whole tones. From this point of view the score of Pelleas und Melisande is an essential moment in Schönberg’s expressive clarification, as he himself recognized in his Harmonielehre (1911): “The fourth chords appear here isolated only once to express an atmosphere whose peculiarity led me against the desire to find a new means of expression. Yes, against my will, because even today I remember that I hesitated to write this harmony, but I could not do without it given the clarity with which it was imposed on me”.

The modernity of the harmonic solutions, together with the richness of the contrapuntal fabric and the boldness of the timbral inventions, represents however only a part of the elements that make the greatness, not only quantitative, of this work. The underlying program is not resolved in external intent, purely descriptive, dramatic or lyrical, but of the drama reproduces the inner unfolding, keeping firmly the imprint of a symphonic form modeled; in addition to the Wagnerian principles of the leading motives, on the cornerstones of absolute music.

Sibelius composed the stage music for the first performance in Finland in the translation of Bertel Gripenberg. For the Swedish Theatre of Helsinki Jean Sibelius’ “Pélleas et Mélisande”, suite per orchestra Op. 46 is one of the most important events on the bill and the success of March 17, 1905. it is confirmed in the immediate 18 subsequent performances. Sibelius, in that same year, reorganizes the ten musical paintings in an orchestral suite formed by nine movements that he publishes as Opera 46; a work of great refinement, of high pathos, never shaken by strong dramatic contrasts, The suite is considered to be one of his finest pieces of music, although he does not enjoy much enthusiasm.

Sibelius resumes with some slight modification the music of the ten paintings, except the ninth; the song “The three blind sisters”, on stage sung by Mélisande, becomes an instrumental piece. Then the score is transcribed for the piano only, but excluding the third movement “By the sea”.

The initial movement, “Alla Porta del Castello” (Vid slottsporten), opens with a short theme introduced by the strings and then taken up by the winds; the section, probably the darkest of the whole suite, closes with austerity.

Mélisande” is presented by an English horn solo; a dark melody describes the meeting of Golaud and Mélisande in the forest, next to a spring. In the short interlude that follows, “By the sea” (På stranden vid havet), the two characters watch a sailing ship that moves away from the horizon.

In the fourth piece of the suite, “A fountain in the park (En källa i parken)”, a hint of waltz opens the scene in which the two lovers walk together to the fountain; here Mélisande drops the ring given by Golaud. The dense sounds of the strings presage the subsequent sad events. Introduced by the English horn, the song “The Three Blind Sisters” (De trenne blinda systrar) takes the form of a medieval ballad.

The sixth movement, “Pastorale”, is a very fine chamber weaving entrusted to woods and arches.

“Mélisande all’arcolaio” (Mélisande vid sländan), third last piece of the suite, is a long, intense movement shaken by the irregular rhythms of the clarinets and the oboe; it is followed by a short “Intermezzo” (Mellanaktsmusik) which has the task of increasing the emotional intensity of the final piece.

The “Mort de Mélisande” (Mélisandes död), the tragic closing of the love story, is a long and moving elegy that slowly vanishes into thin air.