10th January, in 1833, Felix Mendelssohn’s cantata “Die erste Walpurgisnacht” (“The First Walpurgis Night”) premieres in Berlin. Today we discover the mystical symbolism of Mendelssohn’s choral masterpiece.

Ominous, demonic, and subversive adjectives are adjectives that can describe a lot of the music of the Romantic era (especially many of the Faust scenes from that period), but they are probably not the first words that come to mind when asked to characterize the music of Felix Mendelssohn. No, for that matter, Mendelssohn is often viewed as one of two things: as the author of one of the most exquisite and untouched songs of the 19th century (his random score to the Dream of Half a Year Night, with his impressively transparent memories of Shakespeare’s fairies and their world, is secondary only because of this quality) or, jokingly (and dishonestly) by Bernard Shaw, guilty of “childish glove tenderness … ordinary sentimentality and … despicable oratorio.” But none of the points of view – and especially the last – comes close to providing the composer Mendelssohn with full measure of justice. The fact is that Mendelssohn remains one of the most underestimated composers in the West, although after his death his music and reputation ran into rather great difficulties.

Everything seemed to come easily to him. Born into wealth and privilege, he didn’t had difficulties in education and financial support. Mendelssohn’s adolescent triumph – the brilliant Octet and the extraordinary Overture to the Midsummer Night’s Dream – proclaimed him the most remarkable composer in Europe since Mozart and set an almost impossible bar for his later work.

And yet, the best of his late music, even if it does not surpass these two significant points, is at least very close to their coincidence. His five symphonies do well in mixed degrees by number, although the middle three have a fairly powerful punch and exhibit the same forward-thinking intelligence found in German symphonic music from the 1820s and 40s. In the Third, Mendelssohn’s play with structure – each of her five movements is connected and connected, thematically – foreshadowed the work of Schumann, Wagner, Bruckner, Mahler and others.

The Fourth Symphony, arguably in chronological order, the most popular symphony to appear in the repertoire between Beethoven’s Ninth and First, follows one of the more bizarre harmonic schemes in the canon, ranging from A major (in the first movement) to A minor (in the last).

Mendelssohn’s chamber music – and the vast amount of it – remains impressive and powerful, especially the E and F string quartets, the last of which was composed in the last months of Mendelssohn’s life in 1847. The eight books Songs without Words (whose immense popularity, paradoxically, made it something suspicious) remains among the most charming, flexible and idiomatic collections of piano music.

His secular cantata, “Die erste Walpurgisnacht”, is as excellent, deep and reminiscent of a work as any of those he wrote, establishes the text of the greatest German romanticism writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Mendelssohn met Goethe three times; after their last meeting in 1830, he began to stage Goethe’s 1799 ballad, which recounts an eighth-century pagan ritual celebrated in the face of Christian oppression.

Topologically, this is the opposite of the later great sacred works of Mendelssohn, but thematically, there is a connection between them all, their studies in duality, probably driven by Mendelssohn’s own complex upbringing, partly Jewish, partly Christian.

For Goethe, too, the poem addressed something of a timeless theme. “The principles on which this poem is based,” he wrote, “are symbolic in the highest sense of the word…in the history of the world, it must…recur that an ancient, tried, established…order of things will be forced aside…and…pent up within the narrowest…limits. The intermediate period, when the opposition of hatred is still possible and practicable, is forcibly represented in this poem, and the flames of a joyful and undisturbed enthusiasm once more blaze high in brilliant light.”

To this day, people throughout Northern and Eastern Europe continue to scare away witches and demons on the evening of April 30 with bonfires, gunshots and crackling whips. Officially, these celebrations take place on the eve of St. Walpurgis, an 8th century missionary revered for her kindness and mercy during Charlemagne’s bloody wars.

The church may have decided to honor her on this day in order to supplant an older, pagan holiday that welcomed the arrival of spring. Indeed, the traditions of Walpurgis Night are based on the belief that this is the most vicious night of the year; that’s when witches fly into the mountains to worship Satan with blasphemous orgies.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is known to have included the organistic Walpurgis Night in Part I of Faust, repeatedly returning to this topic in his work. In 1799 he published a poem inspired by them: “Die erste Walpurgisnacht”. Soon he began to convince his friend, the composer Karl Friedrich Zeltter, to put it to music. Zelter never finished a performance, but decades later his star pupil was graduating.

Felix Mendelsson was born into a wealthy German-Jewish family who converted to Lutheranism. Young Felix met Goethe several times and impressed the poet. Goethe even declared him more gifted than Mozart’s child (the long-lived Goethe was one of the few to see them both perform live).

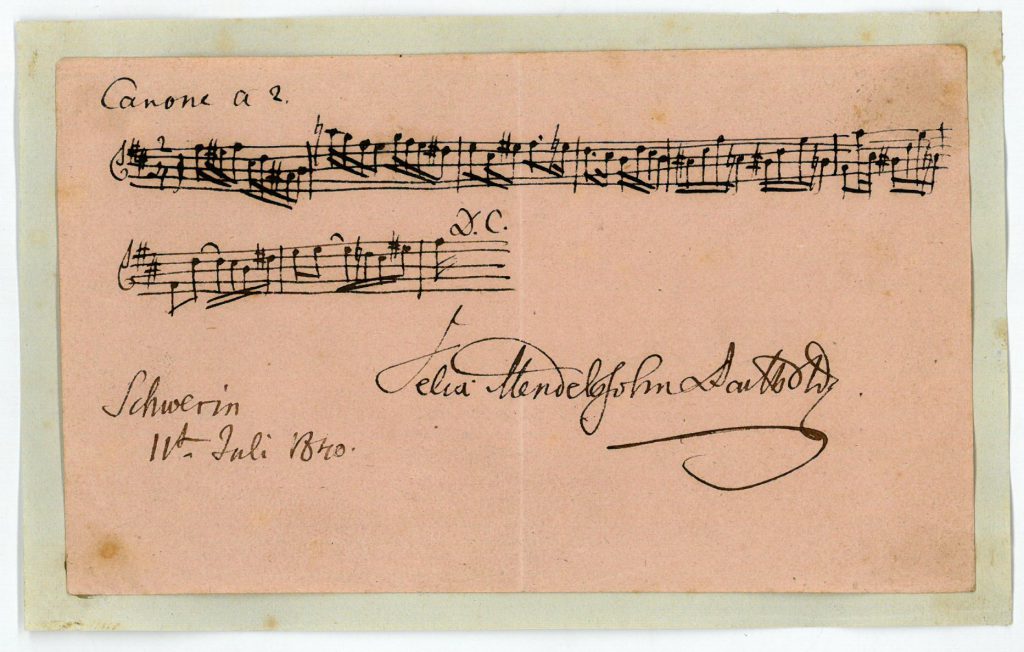

In 1831 he wrote to his sister Fanny:

“[…] I have halfway composed Goethe’s ‘Die erste Walpurgisnacht’ […] a grand cantata with full orchestra. […] when the watchmen make a ruckus with their prongs and pitchforks and owls, there is also the witches’ spookiness, and [you] know that I have a particular fondness for that […]”

Although he corresponded with Mendelssohn when the work was written, Goethe unfortunately passed away almost a year before its public premiere on January 10, 1833. Despite the success of the work, Mendelssohn periodically edited the work until 1843. Mendelssohn’s friend, French composer Hector Berlioz called it the best thing Mendelssohn has done.

Perhaps the most impressive part is the chorus, in which heathens disguise themselves and scare Christians away:

Kommt mit Zacken und mit Gabeln

Wie der Teufel, den sie fabeln,

Und mit wilden Klapperstöcken

Durch die leeren Felsenstrecken!

Kauz und Eule

Heul in unser Rundgeheule!

Come! With prongs and with pitchforks

Like the Devil of their fables,

And with noisemakers

Through the barren rocks!

Coot and owl

Howl in our round dance!

The ballad – and Mendelssohn’s cantata – approaches these themes, however, not gloomy or gloomy. On the contrary, they are saturated with humor and irony. The cunning succeeds, the oppressors (temporarily) flee, and when the poem and poem are over, the heathens are left alone to celebrate their old rituals and the new season in the warmth and light of the sun.

Musically, Mendelsson created the score with great subtlety and depth. The music is surprisingly dull, smoothly moving from the stormy turbulence of Overthur to the melancholic lyricism of the first chorus “Es lacht die Mai” (which is associated with the oppression of Druidic traditions). There is a remarkable concentration of expression in his nine movements (with the exception of the Overture): “Es lacht die Mai” easily transitions from its initial lament to the evocative illumination of sacrificial fires (“Die flamme lodre durch den Rauch”) to the unified whole of unshakable hope (“So wird das Herz erhoben “) with extraordinary fluency and direction – not worth wasting a gesture.

Mendelssohn’s style is often present, but in this context it often sounds more mischievous than ever, as in the choir “Vertheilt euch hier.” There are echoes of Weber and Berlioz in his scoring – not to mention the good anticipation of Verdi’s writings for witches in Macbeth – in the chorus, “Kommt mit Zacken und mit Gabeln,” during which the druids begin to put their plan into action. Indeed, “Kommt mit Zacken” should be one of the most gripping five minutes of music Mendelssohn wrote (and there are many excellent five-minute excerpts or snippets to choose from in his output).

Walpurgisnacht also has a large dose of irony: the noble chants given to the Druids and their priest at several points (including the final of the work) would not be out of place in Elijah or especially Paulus. In fact, this finishing touch once provoked a viewer who apparently didn’t pay enough attention to Mendelssohn after performing the play and thanked him for “a beautiful, redemptive and uplifting Christian choir at the end.” Although, of course, this is not at all the case.

Die Erste Walpurgisnacht certainly does not reinvent the musical wheel: in terms of form, instrumentation and harmonic vocabulary, it is essentially traditional. Nevertheless, this work, thanks to the close identification of Mendelssohn with the themes of the text and its author, lives and breathes in a special, intense way. For that matter, Die Erste Walpurgisnacht suggests that oratorios don’t always do this, just how powerful the opera composer Mendelssohn could be if he possibly lived longer.

Walpurginasta’s dramatic feeling (undoubtedly aided by the directness of Goethe’s verse) is striking in its focus. The music, with its wide stylistic breadth and full integration with the history that it accompanies, is one of the best and most inspirational Mendelsson has ever written, completely worthy of comparison with Midsummer Night’s marvelous Dream, with which it bears quite a few similarities. For this reason alone, it should be heard much wider than it was received.

The form is not published.