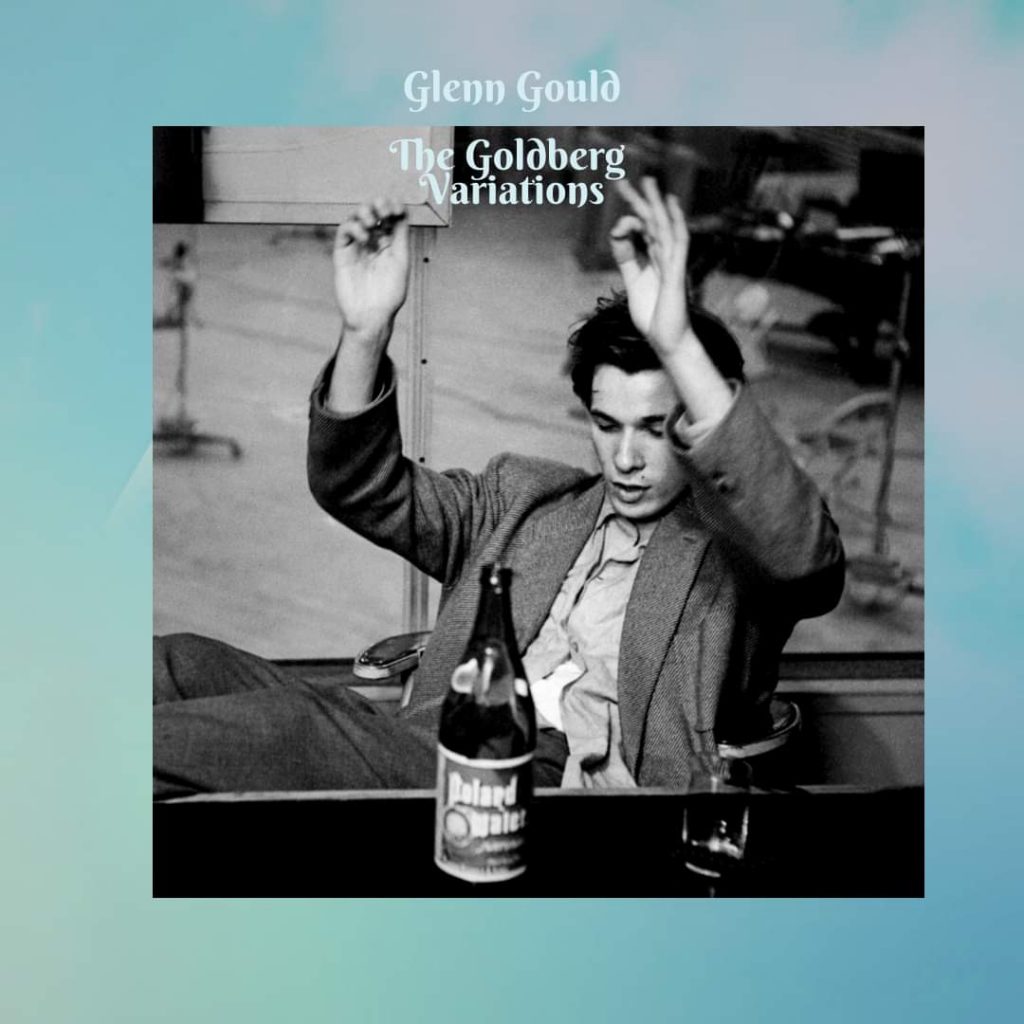

The exceptional recordings of J.S.Bach’s composition by the genius Glenn Gould have brought the new breath of baroque music in the modern era. Gould has produced two famous studio recordings by Goldberg Variations. His first was in 1955 when he was only 22. The second was quarter of a century later, in 1981, when it was coming to the end of its life.

We suggest you to listen to the audio recordings of 1955 and 1959. To compare the creative evolution of the pianist to see the documentary-concert of 1981. Let us make some observations about the significance of Gould’s first interpretations in the history of Bach’s discovering.

The first recording of Gould for Columbia playing Bach as if someone had cut the curtains and thrown the windows into a dark and suffocating room. The crtitics were thrilled; the release broke all records and is still considered one of the top ten classic recordings of all time.

- Variations Goldberg in G Major, BWV 988. Glenn Gould, piano. Studio Recording 1955

Aria (00:00) Variatio 1 A 1 Clav (01:52) Variatio 2 A 1 Clav (02:37) Variatio 3 canone all’unisono (03:15) Variatio 4 A 1 Clav (04:09) Variatio 5 A 1 Ovvero 2 Clav (04:39) Variatio 6 canone alla seconda (05:16) Variatio 7 a 1 ovvero 2 Clav (05:50) Variatio 8 A 2 Clav (06:58) Variatio 9 Canone Alla Terza. A 1. Clav (07:44) Variatio 10 Fughetta. A 1 Clav (08:22) Variatio 11 a 2 Clav (09:05) Variatio 12 2 canone alla quarta in moto contrario (09:59) Variatio 13 a 2 clav (10:55) Variatio 14 a 2 clav (13:06) Variatio 15 canone a la quinta in moto contrario a 1 Clav. Andante (14:05) Variatio 16 ouverture a 1 clav (16:22) Variatio 17 A 2 Clav (17:41) Variatio 18 Canone All Sesta. A 1 Clav (18:33) Variatio 19 a 1 clav (19:20) Variatio 20 a 2 clav (20:02) Variatio 21 Canone Alla Settima. A 1 Clav (20:51) Variatio 22 Alla Breve A 1 Clav (22:33) Variatio 23 a 2 clav (23:15) Variatio 24 canone all’ottava a 1 clav (24:10) Variatio 25 a 2 clav (25:08) Variatio 26 A 2 Clav (31:37) Variatio 27 Canone Alla Nona. A 2 Clav (32:30) Variatio 28 a 2 clav (33:20) Variatio 29 a 1 avvero 2 clav (34:30) Variatio 30 Quodlibet a 1 clav (35:31) Aria da capo (36:19).

- 2. Variations Goldberg in G Major, BWV 988. Glenn Gould, piano. Live Recording, 1959

Aria (38:33) Variatio 1 A 1 Clav (40:22) Variatio 2 A 1 Clav (41:11) Variatio 3 canone all’unisono (41:54) Variatio 4 A 1 Clav (43:00) Variatio 5 A 1 Ovvero 2 Clav (43:47) Variatio 6 canone alla seconda (44:26) Variatio 7 a 1 ovvero 2 Clav (44:56) Variatio 8 A 2 Clav (46:05) Variatio 9 Canone Alla Terza. A 1. Clav (46:54) Variatio 10 Fughetta. A 1 Clav (47:36) Variatio 11 a 2 Clav (48:19) Variatio 12 2 canone alla quarta in moto contrario (49:17) Variatio 13 a 2 clav (50:16) Variatio 14 a 2 clav (52:27) Variatio 15 canone a la quinta in moto contrario a 1 Clav. Andante (53:25) Variatio 16 ouverture a 1 clav (55:55) Variatio 17 A 2 Clav (57:08) Variatio 18 Canone All Sesta. A 1 Clav (58:01) Variatio 19 a 1 clav (58:42) Variatio 20 a 2 clav (59:28) Variatio 21 Canone Alla Settima. A 1 Clav (1:00:19) Variatio 22 Alla Breve A 1 Clav (1:01:42) Variatio 23 a 2 clav (1:02:25) Variatio 24 canone all’ottava a 1 clav (1:03:20) Variatio 25 a 2 clav (1:04:24) Variatio 26 A 2 Clav (1:08:40) Variatio 27 Canone Alla Nona. A 2 Clav (1:09:34) Variatio 28 a 2 clav (1:10:27) Variatio 29 a 1 avvero 2 clav (1:11:25) Variatio 30 Quodlibet a 1 clav (1:12:20) Aria da capo (1:13:41).

The 1955’s press release began: “Columbia Masterworks” recording director and his engineering colleagues are sympathetic veterans who accept as perfectly natural all artists’ studio rituals, foibles, or fancies. But even these hardy souls were surprised by the arrival of young Canadian pianist Glenn Gould and his “recording equipment” for his first Columbia sessions. … It was a balmy June day, but Gould arrived in a coat, beret, muffler and gloves.”

Instead of nobly holding his head up with a proper pianist pose, Gould’s modified piano bench allowed him to put his face right next to the keyboard. He started humming loudly when he was playing. He dipped his arms in warm water for up to 20 minutes before taking, and brought a lot of pills.

He also brought his own water bottles, which, for 1955, was yet something eccentric. It is these initial features, widely trumpeted, that have helped to shape the myth of Gould throughout his too short life, the audacious genius that has disturbed everyone around him. Quite rightly, during the twentieth century, there would be no musical reinterpretation more daring than Gould’s first studio recording.

With his 1955 recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, the young pianist made a compelling case for a work that, at the time, was considered an obscure keyboard composition of Baroque music. Gould counterargued and justified of the importance of the piece by taking great liberties with the source.

In addition to playing the work on a piano instead of on the 18th-century era-appropriate harpsichord, Gould rushed tempos and varied his attack with aggression. But instead of appearing as a young impudent, Gould’s innovations reveal an obvious love for the source material. He took the piece’s exceptional status — a theme-and-variation work — and realized that it could be performed with modernist vigor, full of wild twists of character.

Gould has improved his famous technique over time, using a individual practice known as “finger tapping” to produce muscular memory in his fingers. Enabling vertiginous bursts of notes with astonishing control and minimal physical effort. Gould pioneered the use of the studio as an instrument by connecting the different takes: finding amazing mood collisions that could help lead to his conception of a work.

In erudite liner notes that accompanied the first LP issue in 1956, Gould writes about the strangeness of Bach’s theme-and-variation work: “…one might justifiably expect that … the principal pursuit of the variations would be the illumination of the motivic facets within the melodic complex of the Aria theme. However such is not the case, for the thematic substance, a docile but richly embellished soprano line, possesses an intrinsic homogeneity which bequeaths nothing to posterity and which, so far as motivic representation is concerned, is totally forgotten during the 30 variations.”

It is a fascinating reading of the piece, also, it is true that the power associated with the culmination of Gould’s Goldbergs is exceptional. When the Aria returns, has something to do with the path taken by the listener since the opening.

Gould makes an argument for his own radical vision of how the piece should be played. He sees his own jagged cadence not in defiance of but as a requisite to Bach’s score. Even listeners who put the Goldbergs on as background music are likely to sit up and pay attention when Gould pours it on during Variation No. 5. With that one far edge of intensity established, his ruminative way of handling Bach’s “Canons” is far more seductive. Gould’s lightning-fast runs tend to get all the press, but they cast into sharp relief his poetic handling of the so-called “black pearl” Variation No. 25. The power of Gould’s 1955 Goldbergs comes from the contrasts that Gould chooses to emphasize.

It’s difficult to imagine anyone doing a better job of writing the life story of Glenn Gould than Kevin Bazzana has done in Wondrous Strange…. This superlative biography covers all the important, and many of the trivial, aspects of the Canadian pianist’s relatively brief life, drawing a definitive picture of an unusual musician…. A first-rate view of its subject, one that will send neophytes and devotees alike back to dozens of amazing recordings to hear for themselves the work of a musician whose approach was frequently offbeat, often maddening, but always worthwhile.”

Chicago Tribune

The form is not published.