Shostakovich’s Sixth Symphony came as a complete surprise to the audience. Everything was unexpected: three movements instead of the usual four, the absence of the usual sonata allegro at the beginning of the symphony, the second and third movements similar in a circle of images. “Symphony without a head”, “symphony with two scherzos” – this is how the Sixth was called for a long time. Some critics saw the meaning of the essay in a sharp contrast between the mournful first part and the other two – they interpreted it as an autobiographical contrast to the past painful doubts of a lonely person of an optimistic outlook on life. There were also those who generally refused to perceive the symphony as an artistic whole, believing that the composer had combined the incompatible. Time, however, has shown that the symphony is quite viable, and its content is deeper than even the most benevolent judges assumed.

The coloring of the first, slow part is matte, as if covered with a misty haze. Slowly, evenly, the main theme is presented, in which it is difficult not to feel the mood of mournful meditation. The second theme reinforces the impression – the sad hum of the English horn, the measured rhythm of the bass, similar to the beating of a distant funeral bell. Shostakovich creates an impressive image of numbness, immobility, stiffness, an image that is sometimes mysterious and surreal.

The music of the scherzo was considered by the critics as a failure of the composer. Convinced that this piece – like the finale – was meant to express an “ebullient cheerfulness,” they found it cold and formal. It is indeed cold, joyless, but that was the author’s intention. Shostakovich gave the scherzo a fantastic, ghostly flavor, in which abrupt, scratching, clicking sonorities prevail. Many colorful themes flicker, swarm, slide, intertwine, imperceptibly emerging from the background and dissolving again in it. The music then flows indifferently and indifferently, then it becomes seductively insinuating, then it bursts into sudden explosions of sarcastic laughter. There is no doubt that the scherzo captured the appearance of forces hostile to man; his closest poetic analogue is Pushkin’s Demons.

The twilight, disturbing world of the scherzo is opposed by the world of the finale bathed in sunlight, full of innocent thoughtless joy. In melodic turns, in energetic, perky rhythms, in orchestration, the atmosphere of mass festivities, dance evenings and circus performances, popular concerts and variety shows is conveyed. At the same time, we hear a “panorama” of the musical life of the 30s: an incendiary gallop, a heavy waltz, a vigorous march, and next to it – echoes of the music of Mozart and Rossini. In other words, the motley musical background of the life of a Soviet person, penetrating into all its pores, colored the perception of the world.

Shifting, juxtaposing images of unbearable grief, revelry of evil forces and seething fun, the composer speaks of the proximity of good and evil, beauty and ugliness, nobility and baseness, that life itself is inseparable from death.

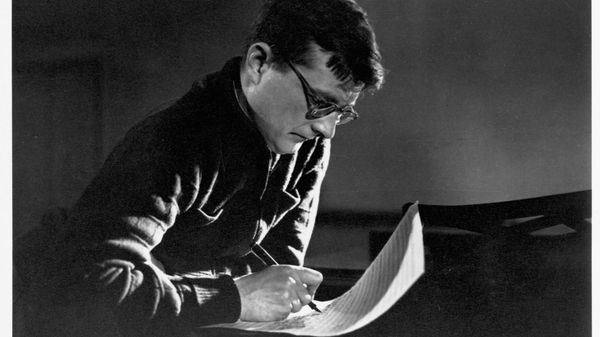

Written in 1939, the symphony was first performed on November 5 of the same year in this very hall. The honored collective of the Republic was conducted by E. Mravinsky.

Get here: